A magical genius from Canada

Saturday, October 5, 2024

The Passion and Puppetry of Ronnie Burkett

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Team Deakins

Friday, April 12, 2024

Behind the scenes with Wes Anderson

By Jackie Daly. Photography by Valérie Sadoun

You will instantly recognise a Wes Anderson movie. The American filmmaker behind The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Fantastic Mr Fox (2009) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is a true auteur. His symmetrical, colour-saturated worlds are portals to the idiosyncratic, his scripts odes to oddballs and eccentrics, brought to life by ensemble casts. Actors such as Edward Norton and Bill Murray return to work with Anderson time and again – as do those who apply their craft behind the scenes on the sets, props, puppets and more. “It’s a family: a circus of people with all kinds of talents, coming together to create Wes’s vision,” says architecture and design photographer Valérie Sadoun, who has been capturing those artists at work since 2016.

Where do Anderson’s worlds begin? “I would say every movie starts in a different way,” says the 54-year-old screenwriter and director from a secret set location. Unable to speak in person during work on his new production, he responds to questions in voice notes, in his distinctive Southern timbre inflected by a Texan drawl. “One story began with a man wrapped in bandages whom I saw in a church in Rome. Another with Akira Kurosawa [the Japanese filmmaker and painter]. Another began with my high school. The world of the movie comes out of the story and the setting and all the research around it. Usually, once I am starting on something, anything I encounter I am more or less pillaging for ingredients. A museum or an encyclopedia or another movie: they all become more or less victims to be stolen from.” And how does he feel about his work being identifiable from a single image? “It depends what mood I’m in!”

Anderson’s sets require months of painstaking preparation. Take, for example, the desert-scorched vistas of his 2023 movie Asteroid City, in which a train chugs across a dusty landscape towards a cluster of red rocks. The scene’s artificiality, what Anderson calls a “desert-desert”, was conceived in miniature before construction began on the gigantic set in Chinchón, Spain. All the sign and lettering detailing involved hours of handpainting by artists Vincent Audoin of studio Lettreur & Gold and François Morel of Morel Enseignes, both Paris-based specialists who have become a familiar double act behind the scenes.

The pair had previously teamed up to paint the old-world shopfronts, vintage signs and lettering seen in the 2021 anthology The French Dispatch, which was shot on location in the “cartoon city” of Angoulême. “It was a kind of dream when they contacted us to take part,” says Audoin. The job found the pair working nonstop, in all weathers, for four and a half months. “It was intense, enlightening, magical,” Audoin adds. “We had the same excited feeling when we heard we’d be working on The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar [2023] – and we’re now on our fourth Wes adventure!”

Anderson is a serial collaborator. “It’s a crazy, huge process,” says Audoin. “Even if Adam Stockhausen [the production designer] is creating and managing a lot for Wes – from design to construction, to decoration work and props – Wes has the final approval. It’s like Alfred Hitchcock. When Wes starts, everything is already set in his head. Nothing is shot if there’s a detail missing.”

I ask Anderson what drives his appreciation for artisanship. “They’re the best of the best. We do a lot of painting!” he says, with the deadpan humour of one of his movies. Likewise, he says of his long-term cast of actors: “If you are lucky enough to have managed to get in touch with some of your favourite actors: well, keep in touch.”

On set, Anderson fosters a sense of camaraderie: “I love a theatre company or a troupe, and I love stories about them,” he says. Sadoun has been friends with Anderson for 20 years and they bonded over a shared obsession with architecture. “I had just returned from photographing architecture in Japan,” says Sadoun of her introduction to his sets. “So when they were shooting in London’s 3 Mills Studios, where they did most of the animation for Isle of Dogs [building 240 sets and 44 stages on site], Wes said to me: ‘You have to come because it is all the architecture that you love.’ It was incredible. From then on I kept going back.”

Anderson “loves” architecture. “I grew up wanting and planning to be an architect,” he says of his early life in Houston, Texas, when he also began writing plays and shooting Super 8 movies with his two brothers. “I love a movie with somebody who has a drafting table in their living room,” he adds – a nod, one assumes, to those early years when he had his own drafting table and would arrange instruments carefully around the edges.

He cites “Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano”, the architects behind the Pompidou Centre in Paris, as inspirations. But to capture the vision for Megasaki City in his stop-motion film Isle of Dogs, he and his team turned to the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange and American Frank Lloyd Wright as references for the film’s retrofuturistic cityscapes.

Erica Dorn has four Anderson films under her belt as lead graphic designer. She takes her cues from the production designer but also has direct contact with Anderson himself, who has sent her down many rabbit holes. She remembers one suggestion that they present Roald Dahl shorts using Dahl’s own handwriting: “Dahl’s handwriting was illegible at times. We went through many rounds of research and development,” she recalls.

Anderson’s eye is famously exacting, but Dorn relishes the process nonetheless. “Every time you do a new film or even a new set you have to become an expert in a very specific area of design. You’ll go from 1950s Midwestern America to a 1920s French prison, each a different world,” she says from Berlin. “There’s tons and tons of research: archives, the films made at that time, what fonts were used and how things were printed and produced.” Dorn has grown in confidence with each project: “After doing a couple of films, I’m starting to get my stride and I’m developing a shorthand – I’m learning to speak Wes’s visual language.”

A huge part of what underpins that language is Anderson’s devotion to the handmade. Arch Model Studio’s Andy Gent, the puppet master behind Fantastic Mr Fox (2009) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) has played an important role here. For Isle of Dogs, his team of 70 puppet fabricators handcrafted more than 1,000 characters (and 2,000 background characters): it’s believed to be the largest number of puppets created by hand for a stop-motion film.

Architecture is realised in miniature by another collaborator: Simon Weisse, the Berlin-based model- and prop-maker, once dubbed “the real star of Anderson’s films”. His team takes on anything from streetscapes to landscapes. Among their many Wes moments is the chugging train in Asteroid City, complete with its tiny cargo, and the 9ft-tall by 14ft-long miniature of the hotel façade in The Grand Budapest Hotel, conceived by Anderson with Adam Stockhausen, who took home an Oscar for the film.

Models (a vital tool in the architect’s repertoire) are integral to Anderson’s style – “We don’t really ever use computer-generated effects,” Anderson says. The aesthetic (and the scripts) are not to everyone’s liking, but most get him (the evidence is out there on TikTok, Instagram and at a recent exhibition of “accidentally” Wes-esque places).

It’s difficult for Anderson to pick a favourite movie from his past projects – his perfectionist tendencies get the better of him: “I don’t really prefer one over another. But there are degrees to which there is more I wish I had managed to fix or get right in the first place on some or all of them,” he says. “I think Isle of Dogs is one that I don’t look back at and see lots of mistakes. And I loved writing it with Roman [Coppola] and Jason [Schwartzman], and I loved our cast, and I loved our animators and puppet makers, too.” Is there anyone Anderson would like to work with that he’s yet to meet? “Tony Kushner and Steven Spielberg,” he says. “But then what would my job be?”

- Books by Wes Anderson

Tuesday, March 12, 2024

The science of Oppenheimer : meet the Oscar-winning movie’s specialist advisers

Reprinted from Nature

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00715-3

11 March 2024

By Jonathan O'Callaghan

Oppenheimer has been praised for its portrayal of the creation of the atomic bomb. Nature spoke to three scientists involved in the film’s production.

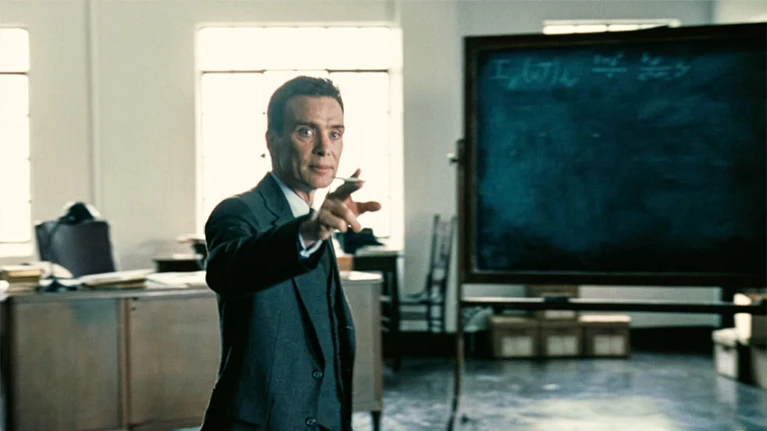

Cillian Murphy picked up the Best Actor award for his portrayal of Oppenheimer.

Credit: Landmark Media/Alamy

Oppenheimer won big at last night’s Oscars, scooping 7 awards out of 13 nominations, including best picture. The film has been lauded for its accurate portrayal of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life and its examination of both the human and scientific toll of the Manhattan Project, the research programme that developed the atomic bomb in the 1940s at Los Alamos in New Mexico.

To ensure the film was as accurate as possible, director Christopher Nolan turned to several science advisers for information on Oppenheimer and his life, and the project itself, which culminated in the Trinity Bomb nuclear test on 16 July 1945 and the subsequent bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, bringing the Second World War to a close at immense human cost.

Nature spoke to three of those advisers for some behind-the-scenes insight into the film’s creation.

Robbert Dijkgraaf, a theoretical physicist and currently the Dutch minister for education, was the director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, from 2012 to 2022, a job Oppenheimer had also held, from 1947 to1966.

Kip Thorne, a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, is a close friend of Nolan’s and had worked with him on a number of previous projects, including the depiction of the gargantuan black hole in the film Interstellar (2014).

And David Saltzberg, a physicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, worked as a scientific consultant for other productions, such as The Big Bang Theory, before applying his expertise to Oppenheimer.

What was your involvement in Oppenheimer?

Dijkgraaf:

In 2021, Nolan wanted to come and visit, to see the place where Oppenheimer had lived and worked for almost 20 years. I also lived in that house and, for 10 years, worked in the same office that Oppenheimer once used. We had a long discussion about Oppenheimer, but also about physics, which I loved.

Thorne:

I spoke with Cillian Murphy about his portrayal of Oppenheimer for the movie. I knew Oppenheimer when I was a graduate student at Princeton, from 1962 to 1965, and a postdoc from 1965 to 1966, so there was some discussion about Oppenheimer as a person.

Saltzberg:

I was called in to help out with the production in scenes that were filmed in Los Angeles. I worked mostly with the prop manager. That involved things like deciding what was on the chalkboards, or what equations Oppenheimer handed to Einstein to show whether the atmosphere would catch fire.

Tell us about some of your interactions with the director and cast

Dijkgraaf:

Nolan visited Princeton twice to tour the premises. I remember we walked from the house to the institute. It’s this beautiful walk with nice trees. I remember telling him it’s the perfect commute, because Einstein and [Austrian physicist] Kurt Gödel always walked along that path. In the movie, Lewis Strauss meets Oppenheimer and he points out the house and says “it’s the perfect commute”. I thought, ‘wait a moment - this is a very familiar scene!’

I was struck that Nolan was really, really interested in what it means to be a physicist.

I also remember he really appreciated the pond at the institute. Quite a few of the scenes in the movie are shot near the pond - it’s a favourite place for many people there. It’s a place to think and contemplate.

Saltzberg:

I sometimes had to explain the physics of a line of dialogue to the actors, enough that they knew the emotional truth of the line and why they were saying it. There was one particular line in the script which was incredibly complicated, about off -diagonal matrix elements and quantum mechanics. Even when I read it I had trouble understanding exactly what it was saying. Cillian really wanted me to explain it to him. We got there, I think, but it was difficult.

A similar thing happened with Josh Hartnett, who played [American nuclear physicist] Ernest Lawrence. Every time he had a spare moment, he would come and talk to me about physics. It was uncanny because he was already in makeup and costume. I never met Lawrence, but I’ve seen plenty of pictures, and it was just eerie. He looked like Lawrence walking around the room.

What did you make of the science in the movie?

Saltzberg:

It was wonderfully accurate. It’s really amazing. Christopher Nolan clearly understood the science. There’s a scene in which Oppenheimer is writing on the chalkboard explaining that nuclear fission is impossible, when Lawrence walks in and says “well, [American physicist Luis Walter] Alvarez just did it next door”. So I had some equations put on the board that Oppenheimer might have had that proved fission is impossible. Most of the audience wouldn’t recognize that, but it made me feel good.

Dijkgraaf:

It was really well done. I loved that the movie consistently looks through the eyes of Oppenheimer. The physics discussions were very good — the right equations were on the blackboards!

What was Oppenheimer like as a person?

Thorne:

He was just a superb mentor, extremely effective. He had enormous breadth and an extremely quick mind. He had this amazing ability to grasp things very quickly and see connections, which was a major factor in his success as the leader of the atomic bomb project.

Dijkgraaf:

He was both a scientific leader and a government adviser. At that time, Einstein, who was quite crucial in starting up the atomic bomb project, really turned into a father of the peace movement. A character who wasn’t in the movie, [Hungarian-American mathematician] John von Neumann, wanted to bomb the Soviet Union, so he was completely on the opposite side. Oppenheimer was trying to walk the reasonable path between those two extremes, and he was punished for it. So I often feel his character generates these mixed feelings. It’s a fascinating example for anyone who wants to be a scientist and play a role in public debate.

Is it satisfying to see a science-based film get such recognition at the Oscars?

Thorne:

It’s wonderful it’s got this level of attention. It’s a film that has messages that are tremendously important for the era we’re in. Hopefully it raises the awareness of the danger of nuclear weapons and the History

Nuclear physics crucial issue of arms control.

Dijkgraaf:

We often complain there’s no content in popular culture. For me, the biggest surprise was that this difficult movie about a difficult topic and a difficult man, shot in a difficult way, became a hit around the world. I feel that’s very encouraging. The hidden life of physicists has become a part of popular culture, and rightly so.